There are a lot of “maybe’s” and “postulating” within this particular article.

I was glancing through the August 2017 magazine edition of Smithsonian, spying the cover story on “The New American Circus” but was more caught up in the “poster art” in the story for some of the world’s greatest human circus performers – not its sideshow attractions – I mean its performers.

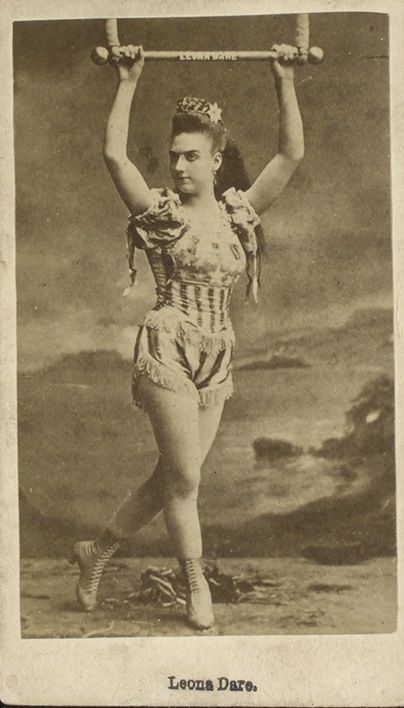

One of the newly created poster art was for a woman named Leona Dare… an American trapeze artist who was once famous for hanging suspended from ascending hot-air balloons. Now we’re talking aviation!

Born in 1854 or 1855, Leona Dare was actually born as Susan Adeline Stuart (or Stewart) – in that classic “parts unknown” kind of way. We just know she was American… and in her later years she lived on Staten Island, NY, as well as Spokane, Washington – where she died.

The Smithsonian “poster” above states that Dare’s father was a Confederate General and that her mother had been killed by a stray bullet during the siege on the infamous Battle of the Alamo… but I have found no other article stating those two interesting facts.

I’m not calling the Smithsonian magazine into question… I’m just stating what I know and don’t know.

For one… didn’t the Battle of the Alamo occur between February 23, 1836 – March 6, 1836? I mean, I’m not American so maybe you guys use a different calendar system than Canada….

If Dare’s mother died at some point in time during the battle in 1836… how the heck did she give birth to Leona in 1854 or 1855? Forget the long pregnancy or thoughts of necrophilia. Oh… now I can’t. Dammit.

I won’t question the Confederate General stuff… except that it is possible he (her father) was involved in the U.S. civil war in the 1860s when Leona was 10, and when his wife had been dead for almost 30 years… Maybe a first wife died at the Alamo… and a second wife was actually the mother to Leona? That makes more sense…

Or… maybe Leona’s mother WAS killed at the Alamo… just not during the Battle of the Alamo. You or I could easily have been shot at the Alamo too, if someone pointed a gun at us during a 21st century tourist visit… and while I’m providing the Smithsonian with ample excuses to award me a No-Prize, I’m unconvinced that the information provided on that “poster” is 100 percent correct.

However… (another attempt at a Marvel Comics No-Prize), it is also possible that the Smithsonian created the data on the poster to mimic circus-era excitement and provide a laugh to the sharp-eyed Canadian visitor to the magazine – a mix that ensures a sucker is born every minute to those who didn’t notice it…

Still… one might assume that the magazine would have stated there was an “inside joke” at some point within the article.

Where did the Dare name come from, and why don’t we believe her surname to have been Stewart? Well, she learned acrobatics from brothers Thomas and Stewart Hall… who sometimes billed themselves as the Dare Brothers.

Where did the Dare name come from, and why don’t we believe her surname to have been Stewart? Well, she learned acrobatics from brothers Thomas and Stewart Hall… who sometimes billed themselves as the Dare Brothers.

However… to be fair, there was a James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart who was originally a United States Army officer from Virginia, who later became a Confederate States Army general during the American Civil War. History is cool, eh kiddies?

Stuart? Stewart? See – J.E.B. Stuart and or Stewart Hall, one half of the Dare Brothers…

See… Stewart is in there, as is Dare. It all sounds like an “acquired” name to me.

In 1871 Susan married Thomas Hall (one of the Dare boys)… in either New York City or New Orleans… I love Circus folk… that whole “from parts unknown” stuff… of course, maybe people just never saw the need to brag about such things on Twitter back in 1871…

U.S. president Trump says his father was never arrested in the 1920s at a KKK demonstration. Maybe such things such as being a circus performer weren’t talked about much around the family dinner table. If my father had ever been arrested, I wouldn’t know – because such talk has never come up.

However… for anyone running and becoming president, you can bet every purported dark corner of their past has been rundown and checked out. It’s just not talked about.

My best guess as to Dare’s wedding location would be New York, simply because she appeared in a circus there later that year… but that’s neither here nor there, so to speak.

Leona Dare was an acrobat and trapeze artist who, wait for it, would utilize a trapeze that was hung down from a rising hot air balloon.

While I suppose many of the day considered her to be hot, she was indeed considered to be a beautiful woman who was a daredevil… and yet, in none of the photos I saw of here could you ever see any ankle. Her hair could also have used some conditioned to tame those wild locks.

During the 1870s and 1880s, Dare performed with many traveling circuses (is that the plural, or is it circusii?) (Kidding.)

Another one of her specialties was the “iron jaw” routine, where she would hang from a wire just by the strength of her teeth/jaw, and spin around… I’m sure you’ve all seen something similar from modern acrobats.

In August of 1872, Dare was in Indianapolis, Indiana, US of A performing for the first-time ever, a stunt where she was suspended under a hot air balloon, lifting her husband (and performance partner off the ground, holding him by his waistband with her teeth. If you look at the image at the very top of this blog, you can see just what it is I am talking about. As you can see, the person being held needs to be as stiff and straight as possible, which is not as appreciated as the iron jaw part, but in my mind just as difficult.

In another spectacular display, Dare was apparently some 5,000 feet above the ground and doing her personal suspension act with her teeth over Crystal Palace in London, Great Britain in June and July of 1877.

If you look at the poster above and compare it with what is written on the Smithsonian “poster” at the very top, we can see that the Smithsonian has rounded off the size of the crowd in a manner that could make a president flip his lid.

As well… the Smithsonian “poster” mentions that Dare ascends to a height of 10,000 feet… which is double what other websites featuring Miss Dare have dared state.

The poster mentions balloon aeronaut Eduard Spelterini (born June 2, 1852 – June 16, 1931) who took Dare up to perform the stunts.

Spelterini was a Swiss pioneer of ballooning and of aerial photography.

Born Eduard Schweizer, he originally hoped to be an opera singer, but after a bout with pneumonia weakened his lungs at the age of 18, he looked around for other avenues, becoming licensed in 1877 by the Académie d’Aérostation météorologique de France as a balloon pilot.

During the 1880s, Spelterini took his balloon solo up in the air up there, and then comfortable enough he began selling rides to customers.

Though he had used balloons built by others, the first one he had a hand in “designing’ was in 1887, when the Parisian company Surcouf manufactured his “Urania” with a volume of 1,500 cubic meters. It first flew in Vienna, Austria on October 5, 1887.

After that, Spelterini moved to Great Britain, meeting Leona Dare in 1888. Their ascents in June and July 1888 at the Crystal Palace in London (see poster above) made them world-famous.

While Dare and “Urania” provided the vehicle for Dare, the balloon basket also provided a ride up for various local journalists, who were given a spectacular view of Dare’s acrobatic exploits which helped create her level of fame via the social media of the day (newspapers).

They toured together through Britain and then continental Europe including Moscow, Russia… with their very last performance together thus being in October of 1889 in Bucharest, Romania.

Spelterini took his Urania balloon from Bucharest to Saloniki (Thessaloniki) in Greece, and then Athens before moving to Cairo, Egypt.

After flying over the pyramids of Giza in early 1890, he traveled to Naples, Italy and then Istanbul, Turkey.

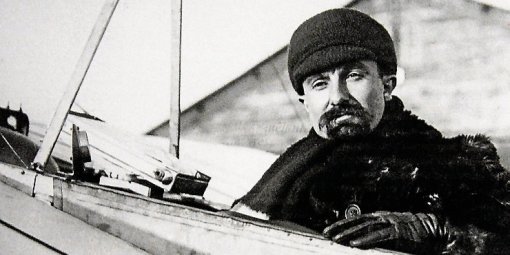

Eduardo Spelterini – August 12, 1912.

In 1891, Spelterini returned to Switzerland, considered then to be “famous” for his aeronaut efforts.On July 26, 1891, Spelterini flew in Switzerland, starting at the Heimplatz in Zurich… and thanks to the crowds that always appeared to see him soar, scientists also took notice, asking if he could take them up so they could conduct atmospheric tests and experiments. Physicians wanted to travel with him to study human blood cells at low atmospheric pressure, while geologists simply wanted to study what the Earth looked like from high above.

In 1893, Spelterini began to take aerial photography. According to one article I saw, the camera equipment weighed anywhere from 40 to 60 kilograms (~88 to 132 pounds), with each photograph requiring a minimum exposure of 1/30th of a second, which doesn’t seem like much despite our modern day ability to snap 100 photos in a couple of seconds via portable telephone of all things… but consider Spelterinin (and other such aerial photographers) were traveling in a balloon… being buffeted by winds…

Perhaps patience is key, but Spelterini became known as one of the premier aerial photographers of his day, winning numerous awards in Italy, France, Belgium and Germany.

Photo by Eduardo Spelterini circa 1903… exact location…. not sure, so I’m not guessing. Okay… Swiss alps?

Spelterini continued to balloon and photograph until The Great War (aka WWI) began in 1914—no one wants a balloon flying overhead when they are at war… as such, Spelterini stopped flying all together, retiring in Switzerland with his wife.

While his aviation exploits had made him comfortably rich, the war and a lack of new income ate into his savings… and the post-war inflation continued to beat at him and others across Europe.

To make matters worse, with the advent of the aeroplane, ballooning fell out of the public’s eye as something spectacular, and everything Spelterinin had accomplished in the past was simply that – the past.

While money is money, he dug out his Urania balloon in 1922 and worked at Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen, Denmark, taking people up in the balloon and posing for photos… which you might understand was something he no longer found as much fun as when he was taking photos of the world.

Having enough of the sour limelight, Spelterni retired again – this time in Austria with his own 300 hen chicken farm, meaning to survive off the sale of their eggs. I’m unsure how that is better than taking people up in a hot air balloon, but by 1926 he agreed with my sentiments at the beginning of this sentence…

Spelterini borrowed some money and rented a balloon in Zurich, Switzerland – hoping to have fun in the air by transporting paying customers for a view. The captive balloon was anchored to the ground with ropes.

Now in his 70s… and while not an ancient age for the 21st century, he was considered pretty old in 1926. His body agreed, as he passed out during a passenger jaunt, forcing his passengers to somehow bring the balloon down themselves in a crash-landing. At least no one was hurt.

That was the last time Speltirini flew… dying in 1931 as an old man with a chicken farm… poor and no longer recalled for his aviation exploits.

As for Leona Dare, who had parted ways with Speltrini in October of 1889… we should back up a week bit.

As mentioned earlier, in 1872 Dare was performing acrobatic feats alongside her husband and former teacher Thomas Hall.

Depending on who you can still find alive to ask (no one, except the Hall and Dare family might have a proper answer), Dare left Hall in 1875, or Hall left Dare… either way Dare was no longer living with Thomas Hall.

She appears to have suffered some sort of physical injury at around that time, and was unable to perform much through the rest of that decade (1870s).

In June of 1880, Dare married Ernest Theordore Grunebaum in London, England… whose family were rich toffs from Vienna, Austria.

Traveling back to Chicago later that year, Dare found out (or was conveniently reminded) that just because one’s husband leaves, or because she left him… a divorce that makes not.

So… since she was still legally married to Thomas Hall, her marriage to Grunebaum was not technically legal. So, after gaining a divorce from Hall in absentia on November 15, 1880, she then legally (this time) re-married Grunebaum in Chicago on November 17, 1880.

A set photo at a studio of Dare and a trapeze… not something taken from this hot babe’s boudoir. Look at that… you might not see an ankle, but you do see a whole lotta leg… no wonder the media and the public loved her. Uh… those boots look pretty tight on the leg…

So… after finally recovering from her accident in the 1870s, the early part of the 1880s was spent using a trapeze and iron jaw skills – but not using a balloon.

Despite the lack of a balloon at this time, in 1884 Dare dropped her partner during a show in Valencia, Spain… he died.

However… I found another reference to another similar occurrence, which has me wondering if it’s the same issue, but with different facts, or two different incidents.

The other story says that in 1884 while suspended by her feet from the roof of the Princess Theatre in London, she held a trapeze bar in her teeth. A male performer was holding on to the trapeze bar with his hands… apparently some newspapers (so the story says) say she had a nervous fit and her mouth released her tooth grip on the bar… and down went her partner. The story continues that it is unknown if the performer survived the fall, but the incident caused Dare to suffer a nervous breakdown of her own.

Which horrific incident is correct? The first, the latter – both? Spain or London?

The first story which declares the partner died is referenced in the Leona Dare Wikipedia entry citing the New York Times, November 23, 1884; and second story is in The (London & Provincial) Entr’acte, December 13, 1884.

Okay… if the accident occurred in London, England… why did the The (London & Provincial) Entr’acte newspaper only report on it some two weeks after it was reported on by the New York Times newspaper an ocean away?

Let’s just say that Dare dropped a partner… she felt like crap for a while… eventually got better and renewed her career.

Since the show must go on, Dare found and trained another partner and continued her act and all was status quo until she teamed up with a Swiss balloonist in 1888.

We’ve covered that aspect of their act and life up above…

In 1890, and with another balloonist, after a balloon she was attached to began to drift away, she apparently purposely lost her grip of the trapeze and fell a distance to the ground, breaking her leg.

Since details are sketchy at best, I’m going to hypothesize that the balloon Dare was attached to lost its pilot… perhaps he himself fell out of the balloon from a low height… and seeing that, Dare released her trapeze grip and fell to the ground rather than be swept up pilotless into the sky.

Does anyone else have any idea of why Dare would have dropped from a balloon drifting away?

By 1894 or 1895, Dare gave up her acrobatic craft and retired to Staten Island, New York, US, though it is reported she died after moving out west to live with her daughter in Spokane, Washington state on May 22/23, 1922.

Her death date is a perfect bookend for Leona Dare… was it the 22nd or the 23rd? It doesn’t matter in the long-run, I suppose…

When I saw that “poster” of Dare in the Smithsonian, I figured it would be a quick couple of paragraphs and done with an easy-peasy article.

Like Leona Dare and every single blog I have done here, nothing is as simple as it seems.

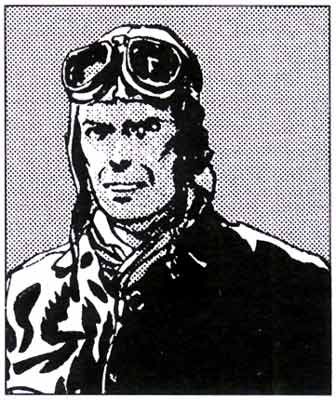

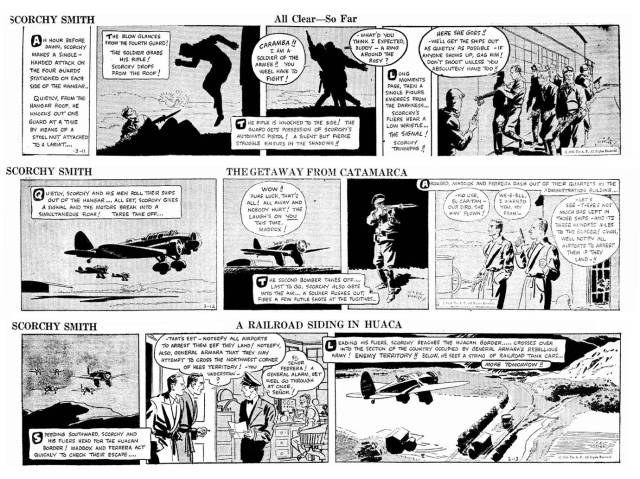

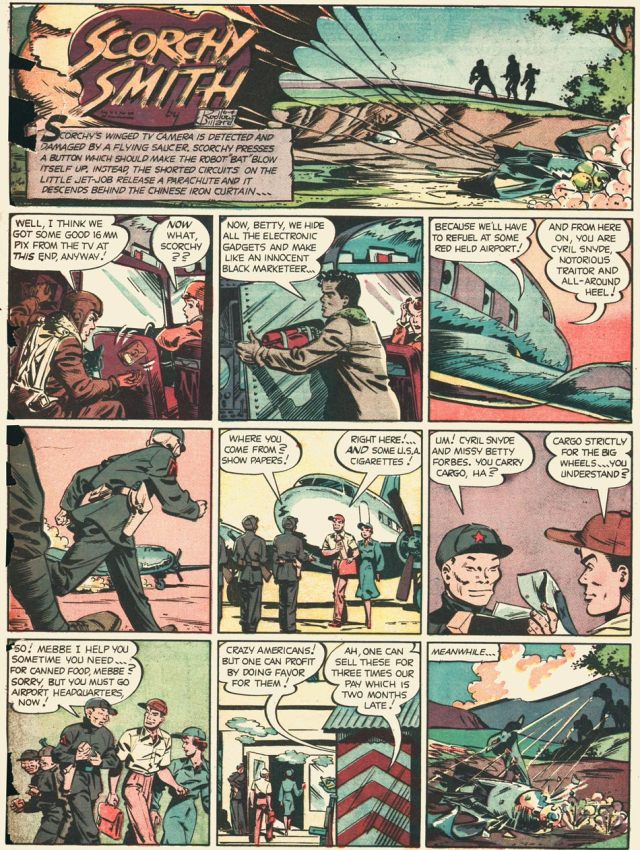

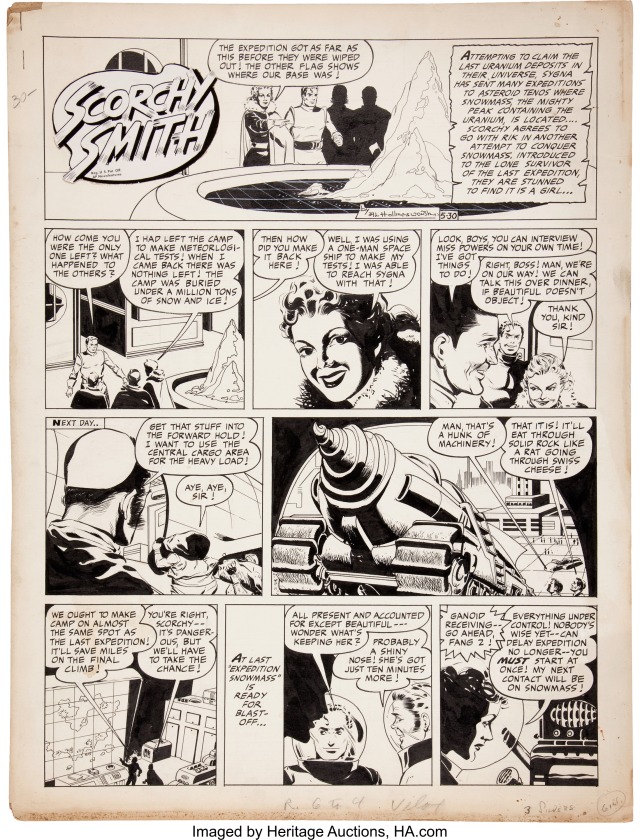

I must admit that while I have heard of Scorchy Smith, I was not around on this planet to enjoy any of his adventures when they first appeared.

I must admit that while I have heard of Scorchy Smith, I was not around on this planet to enjoy any of his adventures when they first appeared.

History Behind The Card: Army Dirigible “Beta.”

History Behind The Card: Army Dirigible “Beta.”

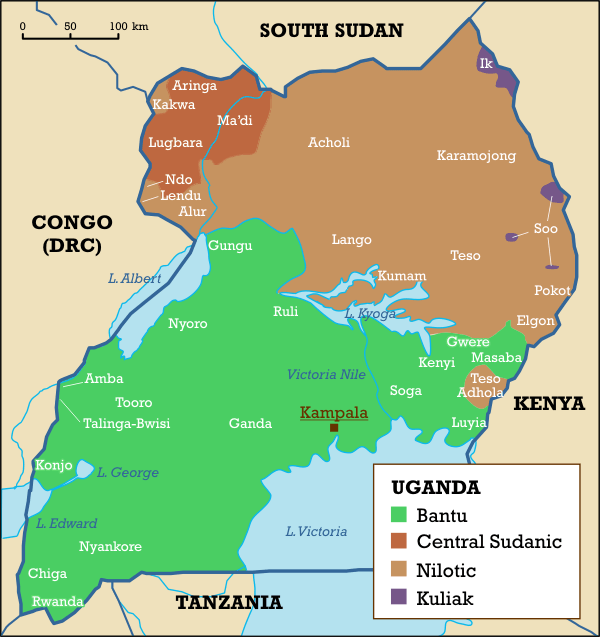

In a western society, one often gets caught up in all things Europe or North America, and tends to ignore the rest of the world. Mea culpa.

In a western society, one often gets caught up in all things Europe or North America, and tends to ignore the rest of the world. Mea culpa.

In my much younger days scientists promised us jetpacks. I want my jetpack! I want to fly!

In my much younger days scientists promised us jetpacks. I want my jetpack! I want to fly! What we have here, is an item at the

What we have here, is an item at the

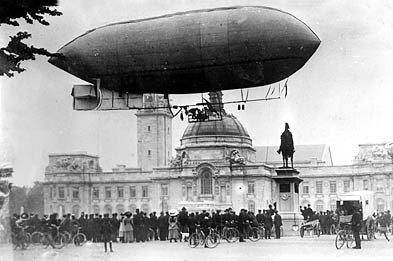

History Behind The Card: Lieut. Jean Conneau (Beaumont)

History Behind The Card: Lieut. Jean Conneau (Beaumont)

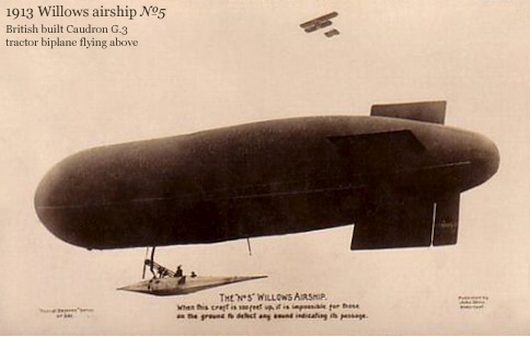

History Behind The Card: “Willows II.” Dirigible.

History Behind The Card: “Willows II.” Dirigible.

Where did the Dare name come from, and why don’t we believe her surname to have been Stewart? Well, she learned acrobatics from brothers Thomas and Stewart Hall… who sometimes billed themselves as the Dare Brothers.

Where did the Dare name come from, and why don’t we believe her surname to have been Stewart? Well, she learned acrobatics from brothers Thomas and Stewart Hall… who sometimes billed themselves as the Dare Brothers.